TestMyBrain began in 2005 as a site for face recognition testing as part of the Prosopagnosia Research Center. It was intended to provide people with web-based tests of face recognition ability that could be completed by people anywhere in the world. At the end of each test, participants would receive their scores, the scores of the average person who took the test, and the cut-off we used in the laboratory for identifying people with potential prosopagnosia, or face blindness.

This was fundamentally a citizen science project (see below) and generated significant interest, leading to a widespread global awareness of face blindness that grew over the decade that followed. Although the project has broadened significantly beyond face recognition research since 2005, we still maintain resources related to face recognition for interested members of the public and people with face blindness as well as people at the other end of the spectrum - super recognizers who have remarkable face recognition abilities!

If you have taken one of the tests above and think you might have face blindness OR be a super recognizer, click below to sign up to be notified about future studies of face recognition by our lab and the labs of our research collaborators. Please note, we share any contact information provided at the link above with other qualified researchers who are studying face blindness or super face recognition ability.

Finally, please read below to learn a little more about our “origin story” in prosopagnosia research and how citizen science can be a critical driver of scientific progress.

A version of this article first appeared in the Summer 2012 issue of the Face to Face newsletter of the Prosopagnosia Research Center.

Prosopagnosia research has made a lot of progress over the last 25 years. That progress has critically depended on the interest and engagement of people suffering from prosopagnosia and their family members - people like some of you. In this article, I want to talk briefly about the way citizen science has driven prosopagnosia research. Citizen science is science done by everyday people rather than professional scientists. Citizen scientists generally have less training and access to resources compared to professional scientists, but they have their own unique set of observations that can contribute to scientific progress in sometimes unexpected and critically important ways.

Many of you who are reading this are citizen scientists. You take part in experiments, share information about yourselves, but most importantly you pay attention to and share your experiences. Our understanding of prosopagnosia took a leap forward at thepoint that scientists began acknowledging people with face blindness as citizen scientists, who understand their own abilities, experiences, and limitations and are willing to share that knowledge with the community of professional scientists in hospitals and universities. I want to take some time in this newsletter to talk about how the contributions of citizen scientists created the field of prosopagnosia research as we know it today.

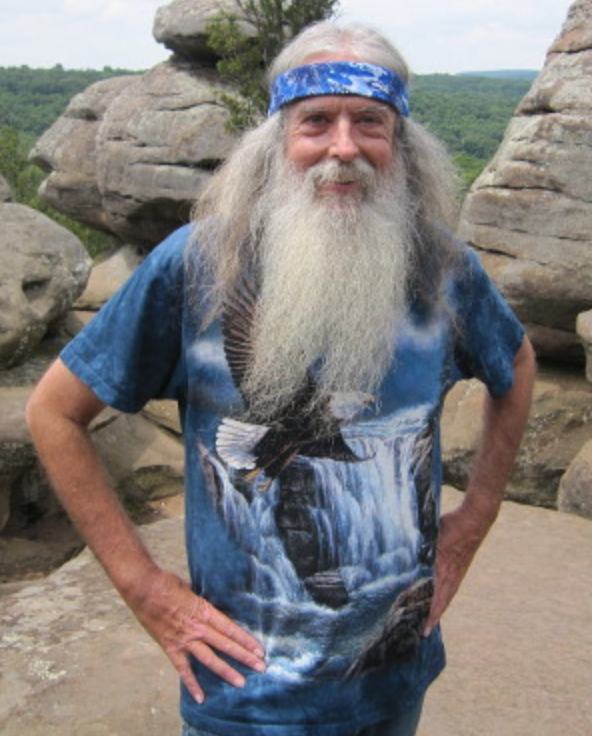

There are probably many versions of this story, beginning in many homes across the world when people with face blindness began connecting with fellow sufferers through the internet. The version of the story I’d like to tell starts with Bill Choisser. Bill Choisser was a self-described “long-haired man in jeans” who lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, had suffered from deficits in face recognition his entire life, and spent many years as an advocate for prosopagnosia awareness. Bill grew up in an Illinois coal-mining town and found that he often recognized other kids by their jeans. He also found when making friends as an adult that he tended to gravitate to other long-haired men in jeans.

Bill didn’t realize he had problems with face recognition until he was in his 40s, sitting in front of the television one day with his partner Larry. They were watching a television program together and Bill expressed frustration that t.v. programs never showed enough of a person’s body and clothes. It was impossible to keep track of characters! Larry looked at Bill and said, “You don’t need all that, you recognize the characters by their faces.” To Bill, this bordered on absurdity; faces were impossible to recognize and all tended to look the same. So Bill took it upon himself to start asking around and observing others to see if they relied as heavily on faces to recognize other people as Larry suggested. This made Bill realize that he was relatively unique in his inability to recognize faces. He went to his doctor and asked whether he might have some sort of neurological problem that meant he couldn’t recognize faces. “There’s no such thing” his doctor said.

This all happened in the mid 90s – the internet was in its preteen years (young, awkward, but with lots of potential) and people were increasingly becoming connected with others in growing online communities. Bill decided to post a message on a forum for neurological disorders. The message said: “I have trouble recognizing faces. Anyone else have this problem?” Then he waited. Soon, he was contacted by someone who reported the same difficulties. Then a second and third person contacted him. A year later there were about 30 people communicating over the internet who reported lifelong difficulties with face recognition with no clear medical explanation. Glenn Alperin, an active member of the group, eventually came across the term “prosopagnosia” in the medical literature. The word seemed to describe the kind of problems that Bill, Glenn, and the other members of their online community were experiencing. But “prosopagnosia” is an unfortunate word: complicated, difficult to remember, and impossible to spell. Bill decided that since people who can’t recognize certain colors are known as “color blind” it made sense that people who couldn’t recognize faces should be called “face blind”. So, in 1997, the term face blindness was coined and is now an accepted term among scientists and sufferers alike.

At the time, the research community was virtually unaware of developmental prosopagnosia / face blindness (that is, face blindness not caused by brain damage in adulthood). The disorder, if it existed at all, was considered very, very rare. There were a handful of reported cases, and it was unclear to researchers whether their deficits may be explained entirely by some form of early brain damage that was difficult or impossible to see on standard CT or MRI brain scans. To any researcher studying prosopagnosia or face blindness, Bill Choisser, Glenn Alperin, and their growing face blind community offered a significant opportunity to learn about face blindness, face recognition, and the way the brain develops. When they approached research scientists who studied face blindness, however, the response was discouraging. Bill Choisser reflects: “None of the researchers we found had any interest in communicating with us. Some ignored us and some were condescending, while from their responses we could tell…we already knew much more about [face blindness] than they did.”

So Bill and others decided it was up to them to learn about the disorder and create web resources for fellow sufferers. For example, in 1997 Bill created a website called “Faceblind!” that described his own experiences with the disorder and his ways of coping. Time passed, the community grew, but developmental prosopagnosia continued to be thought of as an extremely rare, virtually unknown phenomenon. In 1999, Dr. Brad Duchaine (then a graduate student and later founder of the Prosopagnosia Research Center) came upon Bill Choisser’s website and got in touch with him. “I want to work with you to learn about this disorder,” he said. Dr. Duchaine saw the opportunity, but, more importantly, recognized the importance of learning about face blindness with the community of sufferers. People with face blindness were collaborators: citizen scientists who could partner with professional scientists to learn (together) how and why face recognition was different for people with face blindness.

In the intervening years we’ve learned a lot about face recognition and face recognition deficits: that face blindness runs in families, how variations in other abilities seem to be related to face recognition deficits, and how face recognition is just different for people with face blindness. We are also beginning to understand how face blindness might arise from differences in the way the brain develops. Most startling, however, is the realization that developmental prosopagnosia or face blindness is surprisingly common. Up to 1 in 50 people have face recognition deficits severe enough to qualify them for a diagnosis of face blindness. It’s not quite as rare as scientists thought! And all of these insights began with the face blind community and people like Bill Choisser and Glenn Alperin: people with a unique set of experiences, a healthy dose of insight, and the willingness to break new ground as citizen scientists. We believe that scientific research works best when it involves a conversation between professional scientists and citizen scientists, like many of you. In the case of our work, this is a conversation between face recognition researchers and those of you at the front lines who have first-hand experience of face blindness. So, in summary, thank you for making our work possible. To help us understand this disorder, we ask for your continued collaboration: by observing yourself, observing your own experiences, and (when you get the chance) sharing those observations with us. - Dr. Laura Germine, Ph.D.

Bill Choisser passed away in 2016 at the age of 69. He was a great advocate for public communication around face blindness and citizen science, and we post this article here to acknowledge his contributions to science and scientific research. You can learn more about Bill at his website maintained by his partner, Larry Kenney.